Sweethearts of the West — The Harvey Girls

This is shared from Sweethearts of the West. We’ve shared various articles about Harvey Girls in the past but this may be the most complete to date. Enjoy!

FRED HARVEY AND THE HARVEY GIRLS

By Ashley Kath-Bilsky

During the 1870s, the American West beckoned hopeful settlers, many of whom traveled on a sparkling new iron horse called the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad. But unless you packed a hefty basket of food, chances are you would have been half-starved by journey’s end.

There were some crudely built businesses at various train stops that offered food for purchase, but the selection was mediocre at best. By the time you reached your destination, a constant diet of sinkers (otherwise known as soda biscuits), overcooked beans, and a questionable beverage being passed off as coffee, had most probably wreaked havoc with your digestive system. And as if the poor food selection wasn’t bad enough, travelers were often taken advantage of by unscrupulous business owners who gouged customers with high prices, made them pay for the food upfront, then timed it so the diner had to re-board the train before they could eat it. Disgruntled word of mouth traveled quickly and sorely affected both the Santa Fe’s reputation and profits. Something had to be done, and done quickly.

[Vintage illustration of crowded railroad passenger car – Harpers Magazine, Aug 1885]

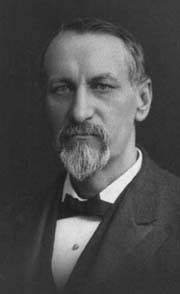

And so it was in 1876 that Fred Harvey, an English immigrant who had a popular restaurant in Topeka, Kansas, entered into a deal – on a handshake, mind you – with the Santa Fe Railroad. A formal contract was written up two years later. The deal? The Santa Fe Railroad built ‘eating houses’ at various towns along its route, and Fred Harvey managed each one by hiring cooks, bakers and kitchen staff, ensuring quality, and training personnel to provide what he was known for back in Topeka, namely Good Food, Good Service, and Good Prices .

Fred Harvey was born on 27 June 1835 in London. In 1853 at the age of 17, he immigrated to the United States, where he worked as “pot walloper” or dishwasher in New York City. Yet he possessed great ambition and was not afraid to work hard. He moved from New York City to New Orleans where, after surviving a bout with Yellow Fever, he relocated to St. Louis. Years later, while working in the rail mail transport, he saw that good food and good service was greatly needed by train passengers. So, in 1875, Harvey opened his first restaurant in Topeka, Kansas.

By 1887, the Santa Fe had built 24 Harvey Houses as far west as San Bernadino, California, and anyone traveling aboard the railroad was told they would find superior food along their journey with just these four words, “Meals by Fred Harvey”. However, there were times when civilized behavior in the Wild West was often tested and rules had to be strictly enforced.

One recorded incident occurred when a group of rowdy cowboys actually rode their horses into a Harvey House located in Las Vegas, New Mexico. Fred Harvey stepped forward and announced, “Gentlemen, ladies dine here. No swearing or foul language is permitted. You must leave quietly at once.” Believe it or not, the cowboys, heads bowed with shame, left…along with their horses.

[Pictured – Topeka Harvey House, Courtesy Kansas Historical Society]

It comes as no surprise, therefore, that Fred Harvey has often been called the man who “civilized the West”…at least inside a Harvey House. For example, all men in the dining room were required to wear a coat. He strived to bring proper English manners to the American West, and his rules of strict conduct also included his staff. In 1883, when he noticed the male waiters often came to work late, usually with a hangover, and would fight on duty, it was wholly unacceptable. He fired the entire staff at a Harvey House in Raton, New Mexico. Not having much confidence in the reliability of male waiters any more, Mr. Harvey took an unprecedented move and decided to hire only female servers for all the Harvey Houses. Ads were placed in newspapers throughout the Midwest.

“Wanted: Young women 18 to 30 years of age, of good moral character, attractive and intelligent, to waitress in Harvey Eating Houses on the Sante Fe in the West. Wages, $17.50 per month with room and board. Liberal tips customary. Experience not necessary. Write Fred Harvey, Union Depot, Kansas City, Missouri.”

Thousands of ladies sent in their applications. Those contacted for a personal interview were all but cross-examined by Alice Steel at the company’s headquarters in Kansas City. Every step was taken to ensure that any female hired as a Harvey Girl had an exemplary character above anything else. And each applicant was also required to sign an affidavit swearing to that fact.

One must remember that the reputation of a Harvey House was important, and meticulous care was made in the staff they hired. Respectable job opportunities for moral women in the late 1800s were rare. Being a Harvey Girl was quite ‘the thing’, something that instilled a sense of pride in the young women selected. They were not referred to as a ‘waitress’; they were “Harvey Girls”.

The reasons for becoming a Harvey Girl varied. For most, there were no jobs for women in their community and it provided a means for them to be independent and also help their families. The Harvey House and Hotel provided respectable employment and a safe place to live. And let’s be honest. There were some starry-eyed Harvey Girls who were not only fascinated with the notion of seeing the American West, but had hopes of meeting their future husband there. For all of them, the wages and tips they earned enabled them to be truly independent. While the husband-seeking Harvey Girl might be saving for her bridal trousseau, for others that income provided them with a means of helping their families back home, and paid for them to have an education they could never have afforded before.

Harvey Girls underwent a six-week training period before being assigned to a Harvey House, usually a small one at first. This enabled them to become more skilled and able to handle being assigned to a larger house in a busier community. Each Harvey Girl was trained to properly set a table and to ensure that there were no chips or cracks in any of the glassware. Serving technique was taught: food from the left, beverages from the right. They were not allowed to talk with other Harvey Girls in the presence of a customer, and they were never to argue with a guest. Children were to be complimented whenever possible, and every Harvey Girl was reminded that a kind, sincere smile on their face was essential.

In a time when bawdy houses and saloon girls wore provocative clothing to entice patrons, the Harvey Girl uniform was completely opposite. Fred Harvey wanted no misunderstanding that the young ladies who worked at the Harvey House were very respectable.

Their uniform consisted of a black dress, crisp white pinafore apron, polished black shoes, black hose, and white ribbons in their hair. Inspection was held daily before the staff was allowed to serve customers. The uniform had to be spotless or one would be required to change her clothes. [Pictured is a still from The Harvey Girls, a 1946 MGM musical featuring Judy Garland.]

To ensure their high standards of service and food, organization was necessary for the busy daily schedule of every Harvey House, especially those in larger communities. They recognized a need to gauge how many passengers would come to dine when the train stopped. As such, train personnel would ask each passenger if they planned to visit the Harvey House at the next stop, and would then wire that information ahead. In this way, the Harvey House knew what percentage would be dining for breakfast, lunch, or dinner. A train whistle sounded about a mile outside town to give the Harvey House a heads-up on their arrival. Meals were served efficiently, making sure each customer had time to enjoy their meal. House managers would “calmly announce” when patrons had 10 minutes to finish their meal before it was time to board their train again. But they always assured their customers that no one would be left behind.

Service was so efficient, in fact, that it included a Cup Code . When train passengers were seated, the Harvey Girl attending them would take their drink order. They would then turn the cup to indicate which beverage the customer wanted. A cup turned up indicated coffee; a cup turned upside down meant tea. The china itself was made especially for Harvey House by Syracuse China. Pictured above is the Harvey House Normandy hand-painted pattern of a bowl, plate and cup.

Some locations had a pattern more unique to their location. For example, the El Tovar Hotel’s restaurant on the rim of the Grand Canyon was built by Hopi craftsmen. Opened in 1905, this Harvey owned hotel used the Webster pattern.

Made by Syracuse China, the El Tovar pattern (table creamer pictured left) consisted of gold filigree with a black border on ivory china. Note: Syracuse China began operations in 1871 and still produces china today. They are known for their restaurant, hotel, and railroad dining car china. However, they also made fine china.

The food one could expect at a Harvey House and Hotel was a far cry from sinkers and bad coffee. Such dishes as whitefish filet with Madeira sauce, roast beef au jus, sugar-cured ham, and even lobster salad were served on fine china and linen tablecloths. Fresh foods, including seafood, fruit and vegetables arrived daily in ice-filled railroad cars, and homemade pies were carved into four generous slices, not six. Without question, the vision and contribution that Fred Harvey made as a pioneer of the hospitality industry in the American West was extraordinary.

The fact that Fred Harvey offered respectable employment to women was also unprecedented at the time. And as an author, the history of this time period and the courage and independence of the Harvey Girls has inspired me to write a series of novellas about a group of very special young ladies who sought travel and adventure, a means to earn money respectably, and possibly find love in the American West. Will they find it? You will have to stay tuned to this blog for further updates.

As for Fred Harvey, he was a true pioneer in the hospitality industry. At the time of his death in 1901, there were 47 restaurants and 15 hotels bearing his name. Through his vision and leadership, hundreds upon thousands of people were provided a much needed service on their travels. Many communities also attributed the presence of a Harvey House or Harvey Hotel with bringing prosperity and respectability to their frontier towns. His vision continued under the management of his sons and remained in the Harvey family until 1965.